Fake or Facsimile: Part 5: "Fake Attractions"

- Tom Curran

- Jun 22, 2017

- 6 min read

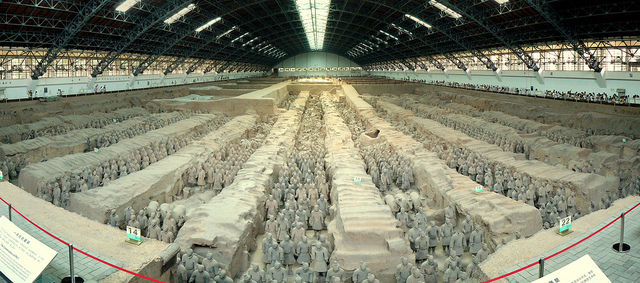

“China’s Terracotta Warriors”, a 7,000 strong Army (with 10,000 weapons)[i] which accompanied the 1st Qin Emperor (died 210 BCE) into the afterlife, probably need to be viewed in situ. Some limited numbers of these timeless guards are loaned out for exhibition,[ii] and the close-up viewing opportunities certainly generate the appropriate amount of “buzz”[iii]—but part of their historic effect has to be their sheer size and quantity,[iv] and the meticulous craftsmanship that went into producing this precisely calibrated Army.

The Emperor’s Army was discovered in 1974 in China’s Shaanxi Province, and the rather unattractively named (and lesser) “Pit 2”, for instance, apparently contains “about 1,000 soldiers, 89 chariots and 400 horses”, in “an overall area of 7,175 square yards”. Among the assembled troops, there are archers, “kneeling crossbowmen” and “foot soldiers with long lances”.[v] So, clearly, an aspect of the artistic effect is coming to terms with the immensity and organization of this underground necropolis—an effect that a small selection of figures can never properly provide.

The current “Age of Empires: Chinese Art” exhibition at the NY Met (until July 16th, 2017) does indeed prominently display a sampling of these ancient terracotta military figures (with their original accompanying weaponry), but it is worth noting that the Met wishes to enhance the experience for its viewers by supplementing the display with “replicas of two half-life-size bronze chariot teams” (my italics).[vi] Even when the central allure is the opportunity to view the “authentic” artifacts, even then there can be a desire to intensify the experience by the use of replicas,[vii] which bring to the exhibit a fuller sense of context.

The discovery of the 1st Emperor’s Army has spawned Terracotta Warrior exhibitions (in Europe and in South Africa, as well as China), all of which fall fully under the rubric of “fake attractions”. Not all of these have met with enthusiastic approval; a particular target seems to be the (admission-charging) spectacle in China’s Anqing City[viii] of a gathering of up to 1,000 of the Army’s Warriors.[ix] But Chinese authorities have also expressed real concern about a recent (but much smaller) exhibition of Warriors in Liège, Belgium.[x] The official “Emperor Qinshihuang’s Mausoleum Site Museum” makes it clear that legal opinion is being sought whether to sue both of these (paying-customer) attractions[xi] for infringement of “registered trademarks and … copyright”.[xii]

In the same vein, a well-established European show (in 2015 it was in Ostend, Belgium) identifies itself as “The Terracotta Army and the First Emperor of China”. This show promises patrons: “the most complete exhibition ever created on (sic) the Terracotta Army” with “more than 300 life size reproductions of statues, chariots, weapons … by Chinese craftsmen from the excavation region…”[xiii] Perhaps, this show’s artistic commitment to mounting replicas of “the same beauty and originality of the original works” is without duplicity and wholly admirable, while still a bit excessive!

I am duty bound to reveal that I am one of those punters who was “confused” by just such an exhibition in Düsseldorf. Let’s just say: this was a truly impressive collection of scores of Warriors, overwhelming in their numbers—but I only discovered that the entire gathering of terracotta figures consisted entirely of reproductions—after I had paid my admission. Apparently, I came off more lightly than those who paid their entrance fee at Hamburg’s Museum für Volkerkünde (Ethnology) to see the “Power of Death” exhibition in 2007, an exhibition which included eight terracotta Warriors and two horses, none of which—as it turns out—could have come from the Emperor’s Mausoleum. The Hamburg Museum’s Director reported that he was assured that these were originals, and the Warriors were supported by “certificates of authenticity”. In fact, these were found to be (excellent) “copies” and not originals. More than 10,000 of the exhibition’s visitors were to be offered refunds.[xiv]

But then, please, bear in mind that not all copies are created equal. It is possible that some of the replica Warriors on display at these various shows actually belong to the category we could identify as “authorized copies”—if we are being generous—and “authorized fakes”—if we are not. In her Guardian article on the Hamburg fiasco, Kate Connolly makes it clear that Warrior copies can be authorized in the sense that they are being produced by “certified manufacturers”.[xv]

But there is another wrinkle here that we should also be ready to explore: the tomb Warriors are themselves, in part at least, assembled from copies and replicas. It appears that face moulds were used to construct the Army’s basic eight styles of faces—this is not a settled number, since there is also a suggestion of “at least ten”[xvi]—but the chief point stands: a mould provided the basics, and the famed unique characteristics of each Warrior were added later, especially it seems with reference to the individually crafted ears![xvii] This craftsmanship has been described as a “mass-production process” in which the general body parts (“arms, hands, and heads”) were manufactured in “modules”, and only subsequently individually enhanced, and “thus made to look as diverse as real army”.[xviii] This is an important consideration that will engage us again in future.

Perhaps you would be interested in acquiring one of these expertly crafted Warriors for yourself? Then I am extremely happy to report that “Life-size” Terracotta Warrior Figures are, indeed, available on Jack Ma’s alibaba website (suitable for your “home and garden decoration”) for between $300 and $600 USD. As with the luxury handbags we discussed earlier, it might be important to discover whether these are modern “factory originals”, so to speak, and supported by suitable documentation, or whether the customer is being offered an “unauthorized” knock-off.

But whatever the case, a sophisticated copy of a (fragile) Terracotta Warrior on alibaba is truly a bargain. The Warrior replica apparently costs only about 10% of the price of a “pre-loved” Louis Vuitton handbag—also available for immediate shipping from the same website.

Next Time: "A Substitute Sistine Chapel"

[i] Asian Art Museum Website (San Francisco): 2013 Exhibition: “China’s Terracotta Warriors: The First Emperor’s Legacy”

[ii] China.org.cn describes itself as an “authorized government portal”; a post on August 31st, 2007 (Wang Zhiyong): “Visitors Increase at Terracotta Army Museum” reports on comments made to China.org.cn by the Museum’s Deputy Curator, Cao Wei: “On September 13 [2007], some 120 warriors will be exhibited at the British Museum in London, the curator revealed. The exhibition will run for seven months.” The report appears to be confusing the total number of exhibits with the actual (and much lower) number of Warriors on loan. The British Museum Website: “The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army” speaks of “120 objects loaned [which] come from the tomb of Qin Shihuangdi, the First Emperor” and suggests that roughly “a dozen complete warrior figures”—of the thousands of Warriors on site—will be exhibited. Jonathan Jones, who visited the exhibition for The Guardian, September 5th, 2007 (“New model army”), counted only 17 Warriors (at that time “the biggest exhibition of these sculptures ever to leave China…”)

[iii] The Guardian, July 2nd, 2008 (Charlotte Higgins): “… Historic year for British Museum…” The “shout-out” for this article reads: “Terracotta army exhibition brought in most visitors since Tutankhamun in 1972”. The 2007/2008 British Museum Exhibition achieved exactly 50% of the 1.7Million visitor turnout drawn in by the Tutankhamun artifacts.

[iv] The number of Warriors is often estimated as numbering 8,000 (e.g., John Roach, nationalgeographic.com: Reference: “Emperor Qin’s Tomb”), since the excavations are ongoing; dailymail.co.uk, May 6th, 2015 (Richard Gray): “China’s terracotta army has new recruits: 1.400 more clay warriors…”

[v] Roberto Ciarla, The Eternal Army: The Terracotta Soldiers of the First Emperor, Revised Edition. Novara, Italy: White Star, 2011; pp. 206 & 208

[vi] The (NY) Metropolitan Museum of Art Website (2017): “Age of Empires: Chinese Art of the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 B.C.–A.D. 220)”

[vii] Smithsonian.com, July 2009 (Arthur Lubow) “Terra Cotta Soldiers on the March”: this article explains that the British Museum 2007/2008 Exhibition included: two replica “intricately detailed, ten-foot-long bronze chariots, each drawn by four bronze horses”; the originals were “too fragile to be transported”.

[viii] MailOnLine, February 9th, 2017 (Sophie Williams): “China is now faking its own famous Terracotta Army”

[ix] criEnglish.com, February 11th, 2017: “Copycat terracotta warriors…”

[x] xinhuanet.com, December 23rd, 2016: “Terra-cotta warriors exhibition attracts visitors in Belgium”

[xi] The Telegraph, February 19th, 2017 (Neil Connor): “China’s terracotta army prepares for war—against replicas”

[xii] Qin Shi Huang Tombs Museum (Statement, released on February 2nd, 2017)

[xiii] www.expo-terracotta.be/exhibition/

[xiv] The Guardian, December 12th, 2007 (Kate Connolly): “German museum admits terracotta warriors are fakes”

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Terra Cotta Warriors: Guardians of China’s First Emperor (Exhibition eBook), National Geographic Museum, p. 27.

[xvii] MailOnLine, November 19th, 2014 (Sarah Griffiths): “Was China’s Terracotta modelled on real soldiers?”

[xviii] ajaonline.org, American Journal of Archaeology, July 2009, Online Museum Review (Zhixin Jason Sun): “The First Emperor: China’s Terracotta Army” (Atlanta, Georgia).

Kommentarer