Flattery — How awesome is that?

- Tom Curran

- Mar 18, 2016

- 7 min read

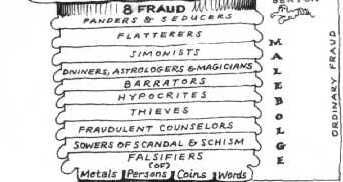

One of the perplexing things about Dante’s Divine Comedy (the dramatic date of which is the year 1300 A.D.) is why flattery is placed so far down into the depths of Hell, when on our way to the 8th Circle (of nine) we pass sins such as miserliness, heresy, tyranny, blasphemy, and usury. This seems an inordinate emphasis upon flattery as a sin, when compared with the destructive effects of tyranny, for instance — treated in Dante’s Divine Comedy as the home of collateral damage and snuffing people out (nothing personal, you understand) because it’s strictly business.

Perhaps it is important to emphasize that Dante’s scheme in this great poem is not about the afterlife: Dante’s interest is the way in which the sins he considers are destructive of individual souls in this life, but even more how these destructive individual sins are ruinous for the human community as a whole. So Dante’s images of the afterlife are fundamentally illustrations of conditions of soul in the lives we lead, and in the responsibilities — mostly due to cowardice — that we shirk.

The depiction of the “sin” of flattery is not particularly edifying — indeed it may be counted as one of the most horrific and repulsive illustrations offered in Dante’s entire Inferno. I assume that the sophisticated readers of this blog (aptly here entitled “It’s a Dirty Job”) will not require a roadmap to the conditions under which the flatterers operate. I remind readers that one of the more delicate ways that flatterers are sometimes identified is as “brown-nosers”. For Dante’s picture, please keep that image in mind, and then just keep going.

Amazingly, Dante’s treatment of the sin of flattery is most present “in its absence”: just 37 verses (out of well over 14,000 lines of poetry — so less than .003% of the verses) are devoted to this venal behaviour. By this means, Dante actually expresses his extreme contempt for this corrupt and corrupting self-promotion, which is often also portrayed as “shoveling the ****”. Less is more, and the less said about this debasement of our language the better.

Unusually for Dante only two individuals (he is equally at home with the historical and the mythological examples) are identified before Dante passes on his way, and he does so virtually without further comment. One of the damned was a contemporary of Dante’s about whom we know practically nothing, except that he was born in Lucca, and that this sinner acknowledges that he made a (presumably successful) career out being a sycophantic toady. The other name mentioned is that of the famous courtesan Thaïs (perhaps best known as the heroine of her eponymous opera by Jules Massenet). Thaïs’s apparently heinous crime is to inform one of her “benefactors”, after the “acrobatics” — if you see what I mean — that he was “awesome”. Dante is not really interested in condemning her for how she makes a living, nor is she placed in the Inferno for that reason. Dante’s concern is with how Thaïs is adept at “hustling” her language, so to speak. The “intercourse”, for which Thaïs is condemned, is social not sexual. From our media-heavy knowledge of an endlessly violent world, it may be hard to see why Thaïs should, in principle, be regarded as a greater threat to the human community than Attila the Hun, for example. However, just consider the overused word “awesome” — a sin of which I myself am a perpetrator: a word which, in essence, inspires “awe”; it may be used, by me for instance, to describe a website, a blue cheese, or a pair of shoes. Language loses all its persuasive power somewhere along the way, and that affects everybody sooner or later.

This may be the appropriate place to reveal that the 8th circle of Dante’s Inferno is the home of fraud — an activity that Dante regards as uniquely human. Flattery, however, is only the second instance of fraud (out of ten) to which we are introduced. The first “ditch” in this 8th Circle is the home of those who corrupt by pandering and seduction. In Dante’s exemplary scheme, clearly there is a very close relationship between seduction and flattery, since the practised seducer has a vocabulary of compliments as part of his corrupting arsenal: “I am lost in the pools of what other mortals call your eyes.” Presumably seduction (of which I have no personal knowledge) involves exaggeration, amplification, magnification, so the suggestive enlargement of real virtues and properly attractive features — and in that context flattery becomes a subset of seduction. But what is actually moving Dante here is, as always, the effect upon the community. Dante fully recognizes fully that for the victim of the famous seducer Casanova the individual consequences are nothing but tragic. But when flattery moves beyond the preying upon an individual and becomes a profession, and a way of life, flattery can bring about the destruction of an entire community. In the introduction to this blog, a word was said about Machiavelli’s importance for a firmer grasp of how the world operates: nothing more needs to be said here beyond informing my readers that the title of Machiavelli’s 13th Chapter of his advice to “The Prince” reads: “How flatterers must be shunned.”

Obviously, the most effective flatterers — and the ones that Dante is seeking to condemn — are those flatterers that have maneuvered themselves through their corruption of language into positions of trusted authority. Please remember that in some respects flattery is even worse than outright lying: for a flatterer to operate effectively, there must be just enough of a truth in the flattery to make it convincing: their fraud is therefore the more complete. Please consider the consequences for all the citizens of a city, province or a country in which the elected leader chooses to surround himself or herself with yea-sayers, sycophants and social climbers. Not only do our leaders then acquire grossly inflated views of their intelligence and abilities, but they never get advice which is of any real value. There is no telling truth to power. The real victims of flattery are the communities being run by leaders who cannot resist the fawning misrepresentation provided by their grovelling retainers, who, in promoting their own self-interest are, in fact, pillaging the common good. To indicate to a prince (or a CEO for that matter) that current policies are disastrous, poorly conceived and potentially destructive of country or company is to fall under the threat of being fired — presumably in Dante’s day being executed was an even more likely potential risk or liability.

To follow Dante’s “descent into Hell” then, the further reaches of flattery lead, completely logically, into influence peddling, including ultimately the corrupt buying and selling of public offices and trust, entirely for one’s own personal gain. The 8th Circle of Hell is, for Dante, the proper home of the unprincipled political lobbyist, who may, by the time we get to the 8th ditch of the 8th Circle, actually be designated as a “counsellor of fraud”. This is very much our world, by the way. Bernie Madoff was able to dupe thousands of both naïve and sophisticated investors, with a promise of guaranteed 15% annual returns on investment — all of which was made possible by the most elaborate Ponzi scheme of this millennium — so far.

The challenge for my friends at AllIn is to provide genuine, positive, creative advice (without applying cosmetic to the blemishes and papering over the cracks). In order to move forward positively in any undertaking, some searching, troubling criticism may be required. All of us, whether clients or employees, bristle when we receive suggestions of oversights, failures, and a lack of dispassionate analysis. The challenges facing us are: first, actually being able to hear the criticism, and then facing the even tougher challenge of knowing what to do about it. However, if you are inclined to be persuaded by my love affair with early modern Italian literature, then you will by now be equipped to hear the obvious point: that surrounding yourself with flatterers is the most certain way to suffer a real loss of power and focus within any form of enterprise whatsoever.

It is an act of courage and character to pay advisers, not for flattery, but for constructive, objective criticism levelled at the self and the operation for which one is responsible. That advisers must be allowed to foreground what is going wrong is a given; otherwise their advice is useless. But my friends at AllIn also face a particularly daunting challenge and obligation: successful criticism is, of course, the provision to the client of the warts, the short comings and the voids. But, in a balanced picture of any management, administration or enterprise, it is the responsibility of advisers also to highlight to the client, what is working and what is working particularly well. Anybody can poke holes; but to shape the criticism with full respect to the success of any particular industry or undertaking — that is a singular gift that we would all be pleased to receive. This challenge requires any firm of consultants to shape their criticism without either minimizing or dismissing the ongoing “awesome” achievements they identify, and the whole package must be delivered comprehensively without ever resorting to flattery.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Dr Thomas Curran is Associate Professor of Humanities at the University of King’s College in Halifax, Nova Scotia. At King’s, he serves as Chair of Faculty, Clerk of Convocation, and Associate Director (Students) of the Foundation Year Programme (FYP).

His chief research interest has always been early 19th-century German philosophy, with a particular emphasis on Hegel’s lectures on the philosophy of religion at the University of Berlin. More recently, his emphasis has shifted to questions of “intertextuality” in Dante’s Divine Comedy — that is, how Dante uses (and transforms) his great precursors (Aristotle, Vergil, St Thomas Aquinas) both to shape his epic poem and to give it a distinctive structure.

Tom is always interested in exploring how modern popular culture and practices can be informed (and reformulated) by reference to the great philosophical and literary tradition that we have inherited from the ancient Greeks.

Comments